From Dr. Charles Carrigan, Professor of Chemistry and Geoscience

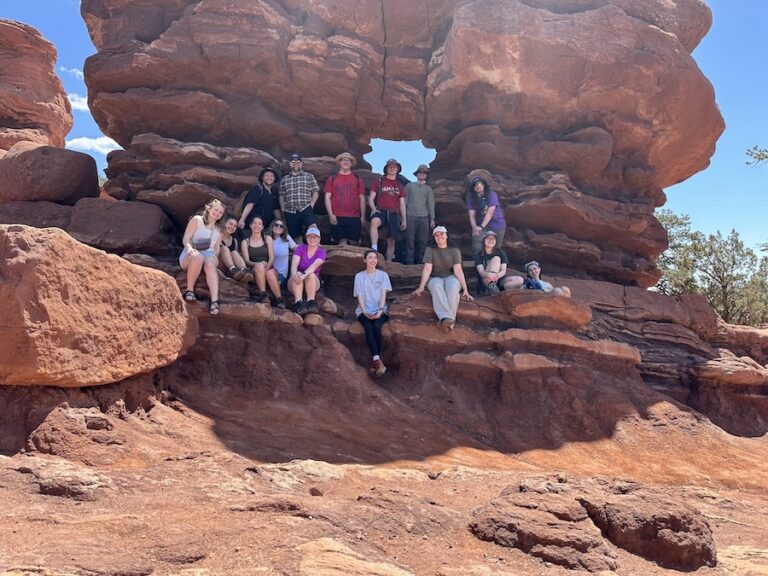

In May 2025, 12 students and I loaded up our vehicles and headed west. Our first stop was Rocky Mountain National Park, just outside of Estes Park, Colorado.

As we climbed a rocky glacial moraine deposited in the last Ice Age, we sat down together. I asked the students to consider what mountains mean to them. For some of them, this was their first time seeing mountains up close, their first time west of the Mississippi. Most of them had never had such a strange question posed for their consideration. For many of them, a mountain was an obstacle, something that loomed large over their lives, something they needed to overcome.

Fast forward, just two weeks later, and I asked them the same question. This time, we were in the shadow of the Sangre de Cristos Mountains, on the Great Sand Dunes of the San Luis Valley. Their answers were much more imaginative and creative than on that first day.

After almost two weeks of driving and hiking through the Front Range and the Colorado Plateau, they had had their eyes open to a world that was much bigger than they had known before. At this point, a mountain might still be a challenge to overcome or an obstacle in their path to avoid. But now, a mountain might also be a remote place of refuge, an intense and powerful force of nature, a journey of discovery, or a sacred place where Earth and Sky meet.

This trip, of course, was not just an eye-opening spiritual journey. They witnessed first-hand the pages of Earth’s history opened in front of them: the stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon. They placed their hands into the depressions of mudstones where dinosaurs once roamed, comparing the size of their own fingers to the massive toes of some of these ancient beasts. They looked up into the cirques where long-flowing valley glaciers, now gone, were once birthed. Together, we climbed hardened layers of gravel that were thrust up high into the air by massive peaks. The students’ knowledge of geology solidified in their minds, as the rocks revealed their own secrets in the way only scientific investigations can uncover.

Our group also saw how the land is protected by the U.S. federal government through the laws, policies and procedures that give us our National Parks and Monuments. They newly understood that there are special places worth protecting, and that it takes all of us, working together, to keep these special places in good shape. The challenges of conservation are real, but our Christian stewardship ethic invites us to lean into the difficult work of tending the garden and participating in God’s renewal of all Creation.

After seeing eight National Parks, four National Monuments and other sites along the way, these students saw the land, and themselves, in new ways. That transformative education is what Olivet Nazarene University STEM programs are all about.

Costs of this trip were supplemented by the McGraw Fund, the Catalyst Fund and the Earth and Space Sciences Special Projects Fund.

From the 2025 STEM Report. Read the full Issue here.